🇪🇸 Spain’s Blackout of April 28, 2025 – A Wake-Up Call for Critical Infrastructure

I found refreshing to read an incident report that is out of the typical I usually had to deal with or others on the area of IT, so I would like to share my learnings on this blog. I found fascinating how same principles apply and found multiple analogies to information systems, so sharing with you what I discovered and hope it can help to inspire you on your system resiliency strategy.

This is based on a public report that the Spanish goverment published a few weeks back.

but first, what happened ? let’s get serious…

On April 28, 2025, at precisely 12:33:30, the entire Iberian Peninsula experienced a blackout of historic proportions. The Spanish and Portuguese grids were abruptly disconnected from the European power network, and for nearly two hours, 100% of the population endured a full zero-voltage event.

This wasn’t just a national event, it was a textbook failure worth dissecting. Not just for what failed, but for how it maps directly to many of the anti-patterns we fight daily when designing resilient systems.

I read into the report released a few weeks back, so I feel intriged about the silence preceeding the report.

🧯 Phase by Phase Breakdown: What Went Wrong?⌗

The official analysis divided the incident into 5 phases:

-

Phase 0 – Precursor Instabilities

The weeks prior saw unaddressed voltage anomalies. Small signs—ignored or minimized. Alert fatigue ? Alert fatigue and cognitive desensitization to weak signals very likely played a role, based on the document, reflects drift into failure pattern. The system didn’t fail suddenly. It eroded predictably and visibly, but the signals were muted over time by habituation, workload saturation, and underestimation of compound risk. Sounds famil, SRE sounds familiar ?According to the report, several pre-incident voltage disturbances and oscillations were recorded in the weeks and months before April 28, with key events on:

- January 31

- March 19

- April 22

- April 24

These incidents were all characterized by system-wide voltage oscillations and reactive power compensation anomalies, particularly affecting key substations and high-voltage lines. The report explicitly says that these events were “registered and analyzed,” but no corrective measures were implemented beyond “limited operational adjustments” - Whatever this means

The same type of issue (system-wide voltage anomalies and oscillations) occurred at least four times before the actual blackout. The report hints at diminishing operational concern over these events because they resolved without incident.

-

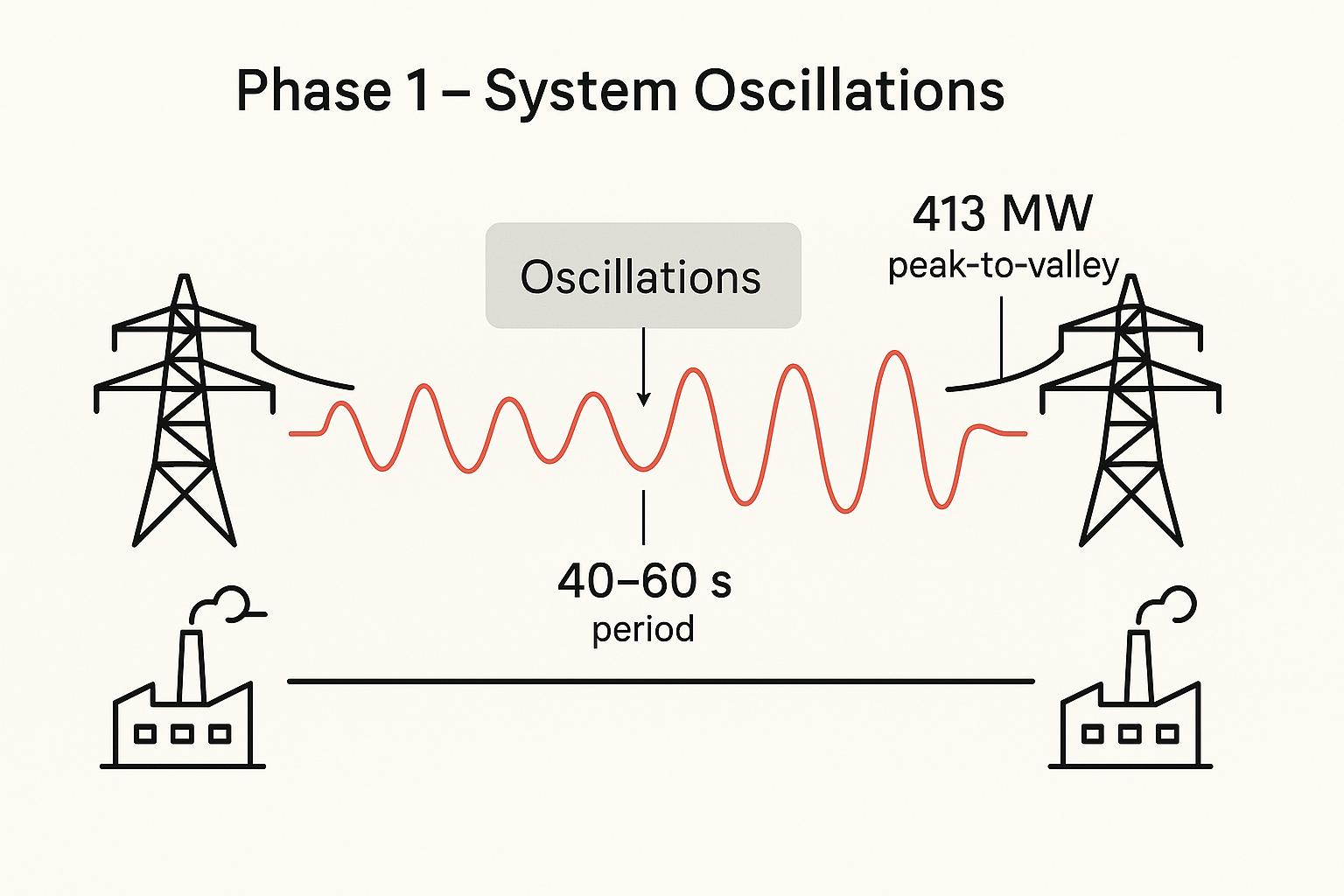

Phase 1 – System Oscillations

Between 12:00 and 12:30, oscillations of 0.2 and 0.6 Hz were detected. Some circuits were reconnected ad-hoc to improve damping (the process by which energy is dissipated from an oscillating, typically as heat, due to resistive forces such as friction or material resistance), but the system was already vulnerable.

The reactive power system was already behaving abnormally, and it appears the team had adjusted expectations downward: abnormal became normal, as stated:

“Durante la mañana del 28 de abril, se producen situaciones de inestabilidad de tensión y comportamiento no previsto del sistema de compensación de reactiva, que ya se habían detectado en otros eventos anteriores (31 de enero, 19 de marzo, 22 y 24 de abril). Estos eventos fueron registrados y analizados, pero no se tomaron medidas correctoras, más allá de ajustes operativos limitados”

Despite recurring incidents, there was no cross-organizational review, no simulation of edge-case scenarios, and no enforcement of system-level preventive checks.

The reports states clearly that the operators were aware of high renewable dependency (82% on the day of the blackout), and yet no proactive reinforcement of traditional generation for inertia support was executed (A signal was ignored). This is critical, as electric grids rely on inertia (the physical property of large spinning masses like gas and nuclear turbines) to maintain frequency stability (50 Hz in Europe). This inertia acts like a shock absorber: it resists sudden changes in frequency when there’s a disruption in supply or demand.

Traditionally, thermal power plants (nuclear, gas, coal) provide this inertia naturally because they use rotating generators synchronized to the grid. When a disruption happens (for instance: a generator trips or demand spikes) stored kinetic energy in those turbines helps keep the frequency steady for a few crucial seconds, giving operators and automated systems time to react.

However, most renewable sources—like solar and wind—don’t inherently provide inertia. They use inverters to connect to the grid electronically, which decouples them from the natural dynamics of the power system. This creates a fragility: when there's a sudden change, the grid frequency can collapse faster because there's no spinning mass to resist it.

All this exposed the grid’s increasing instability through oscillations in frequency and voltage—clear signs that the system was entering a vulnerable state. While operators did respond with network reconfiguration and communication with neighboring TSOs (like France and Portugal), these actions were reactive, fragmented, and slow compared to the pace of degradation.

A good analogy on systems: Imagine a large-scale microservices system experiencing latency spikes and intermittent outages. Engineers begin rerouting traffic and restarting pods, but there's no service mesh enforcing global resilience, no circuit breakers, and logs are scattered across regions. By the time alerts escalate, the event horizon has already passed. The system is still technically “up,” but its integrity is quietly unraveling.

-

Phase 2 – Generation Failures by Overvoltage

This phase was critical because it pushed the system past the point of no return. While Phase 1 had shown signs of instability, Phase 2 triggered an unrecoverable cascade.

Voltage instability became self-reinforcing: the fewer generators available, the worse the control.

Protection systems were uncoordinated: each generator acted individually, not as part of a system-wide resilience plan.

As generators tripped due to overvoltage (Yes, like on your house when the oven and hair dryer are connected at the same time and breaker flips), parts of the grid lost electrical continuity. The grid, normally acts as a single synchronized system operating at 50 Hz, began to break into “electrical islands” (Kinda sections that became isolated from each other)

These islands no longer had a common frequency reference (Each island doing its own thing)

Without this synchronization, each island started to drift in frequency, accelerating instability, then the isolated areas could not absorb or supply enough power, leading to blackouts within blackouts.

This fragmentation is deadly for a power grid: the system relies on tight synchronization. Once that’s gone, automatic protection systems shut down more components to avoid physical damage—making total collapse inevitable.

At 12:32:04, voltage levels across the 400 kV network began rising abnormally, especially in key substations. This was not just a spike, but a progressive overvoltage scenario lasting about 30–40 seconds, with voltages reaching levels beyond the upper operational threshold.

The high voltage caused automatic disconnection of numerous generation units as their protection systems were triggered. These included:

- Combined-cycle gas plants, which are especially sensitive to voltage excursions.

- Hydraulic units, which also dropped off the grid due to protection triggers.

This mass dropout led to:

- A loss of more than 4,000 MW of generation capacity in under a minute.

- Further increases in voltage due to loss of load balancing.

- Dampening mechanisms, such as reactive compensation and tap changers, becoming overwhelmed or inoperable due to the speed and scale of the voltage rise.

Imagine a K8s cluster running a large-scale app. Due to a sudden overload or configuration error, half the nodes start rebooting. Some services remain, but they’re no longer communicating through the service mesh. Without a central control plane, they start accepting requests, interpreting messages inconsistently, and applying outdated configs. You now have multiple conflicting versions of truth—just like electrical islands with no shared frequency. Eventually, consistency breaks down entirely, and you’re left with service crashes, corrupted data, or cascading 500s. Funny huh ?

-

Phase 3 – Collapse to Zero Voltage

The grid couldn’t compensate. Within 18 seconds, a total collapse!

At 12:32:52, approximately 18 seconds after the peak overvoltage, the Spanish electrical system experienced complete systemic failure:

The grid lost frequency synchronization across regions, multiple critical transmission lines and substations tripped in quick succession / domino effect.

Attempts to activate automatic control mechanisms—such as underfrequency load shedding or voltage restoration protocols were too slow, too manual or outright failed.

The system could no longer balance generation and load, and protective systems initiated full disconnection to avoid physical damage.

At this point: there was no longer a functioning electrical reference point in the Spanish grid. From that moment onward, all nodes saw voltage collapse, frequency drift, and islanding without viable recovery coordination. This happens as a consequence of too many generation units had already disconnected in Phase 2. The system had insufficient power to maintain 400 kV and 50 Hz.

Control actions (like automatic reconnections or emergency grid splits) either failed due to timing constraints or were never initiated, the report is not clear on the reasons

Without real-time fallback mechanism for system-wide restoration once regional collapses began.

The lack of inertia (from traditional generators) meant frequency dropped too quickly for control systems to intervene as they should have.

📊 Timeline

- 12:32:04 – Start of voltage escalation

- 12:32:20–12:32:35 – Major generator disconnections

- 12:32:52 – Grid enters full blackout

- 12:33:30 – First signs of manual recovery begin

This window of under 60 seconds illustrates how fast an unbalanced grid can move from instability to total failure once reactive control fails and generation is too depleted.

-

Phase 4 – Recovery

Supply restoration began at 12:33:30 and took until 14:36 the next day to fully normalize.

Root Causes:⌗

Despite initial fears, cybersecurity was not the cause. The root issues lay in systemic fragility:

- Overreliance on Renewable Generation (82% of mix that day), without adequate dynamic voltage control.

- Inadequate inertia in the system, especially with nuclear and gas units offline.

- Weak damping strategies for system oscillations. Manual interventions came late and were insufficient.

- Lack of automatic stabilization mechanisms under high-variability conditions.

- Data blindness and instrumentation gaps—some systems lacked calibrated measurement tools.

Architectural Lessons: Mapping to Bad Practices⌗

From an architecture and BCP lens, this blackout illustrates several anti-patterns:

| Bad Practice | Real Example from 28-A | Lesson |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring weak signals | Voltage anomalies on Jan 31, Mar 19, Apr 22 & 24 were noted but not resolved | Always respect “small” alerts—they’re prequels |

| Distributed responsibility | REE lacked fast enforcement over regional generation units | In complex systems, define final authority |

| Over-complexity without observability | 1,200+ hours post-facto due to unclear ownership of control centers | Visibility must scale with system complexity |

| Poor chaos preparedness | No end-to-end simulation in high-renewable, low-demand contexts | Build and run failure drills in production-like states |

| Human-speed incident coordination | Inter-TSO responses took minutes during collapse | BCP needs machine-speed response, not human-speed |

What Could Have Been Done Better?⌗

The report doesn’t hold back:

- Digital system oversight was fragmented. Too many independent systems with unclear integrations.

- BCP lacked real drills. Simulations didn’t include scenarios of synchronized overvoltage and low inertia.

- Preventable outages. Many thermal units were offline for maintenance at the same time.

- Disaster recovery lacked automation. Manual checks and reactive actions prolonged recovery.

Final Thoughts⌗

What happened in Spain is a cautionary tale for any architect working on critical systems—power grids or otherwise.

This wasn’t a black swan. It was a gray rhino.

⚠️ We knew renewables add instability under specific conditions.

⚠️ We knew distributed control reduces coordination speed.

⚠️ We knew oscillations were emerging more frequently.

Yet action was reactive, not proactive.